Pioneers of Outlaw Country: Wyoming History

Welcome to Pioneers of Outlaw Country: Wyoming History where we dive deep into the rugged, untamed spirit of Wyoming's rich history.

I’m your host, Jackie Dorothy. So pleased to meet you! I am a historian, journalist and memoir coach and you can find me at legendrockmedia.com. I’m the seventh generation of my family living in Wyoming and currently live near Thermopolis on the Wind River Reservation. My passion is to make history come alive!

Many of these stories have been forgotten and the pioneers are relatively unknown. Join us for a journey back into time that is fun for the entire family and students of any age!

This podcast series has been supported by our partners; the Hot Springs County Pioneer Association, the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, a program of the Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources, the Wyoming Humanities, and the Wyoming Office of Transportation.

Pioneers of Outlaw Country: Wyoming History

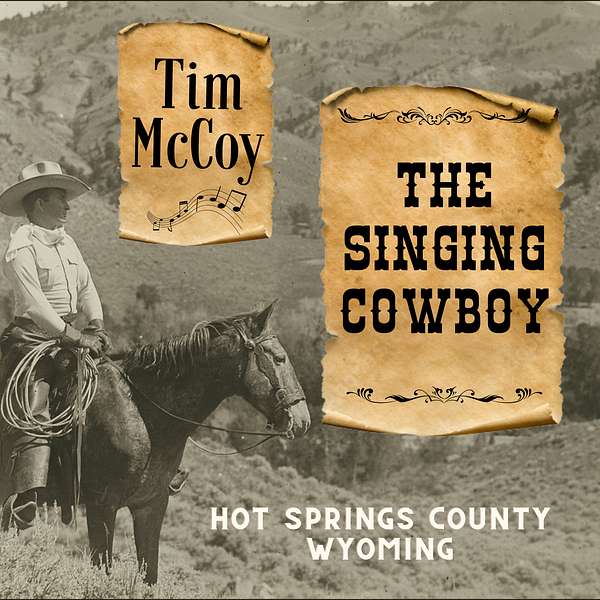

Tim McCoy, the Singing Cowboy

Welcome to the first episode of this 12-part series featuring stories from pioneers of the outlaw country of Wyoming; Hot Springs County.

He was a man of the West. A cowboy, rancher, friend of the Indian warrior, cavalry officer, Hollywood movie star, and showman.

He lived by the adage, “Never look back; something might be gaining on you.”

This son of Irish immigrants was a true pioneer of Hot Springs County, Wyoming.

During his lifetime, Tim McCoy was one of the most famous men who called Hot Springs County, Wyoming home.

In the early days of film, he was one of the Big Four of Hollywood Western Stars alongside Tom Mix, Ken Maynard and Hoot Gibson. He starred in over 100 movies, had his own tv show, won an Emmy and his star is on Hollywood Boulevard.

Today, many people never heard of Tim McCoy even in his hometown of Thermopolis. Tim McCoy’s early years were tied to Hot Springs County and he ranched up Owl Creek at the Eagles Nest for 30 years. He often said that his heart belonged to Wyoming – not the glitz and glam of Hollywood.

Be sure to subscribe so you don’t miss a single episode of this historic series. The stories of our pioneers were brought to you by Hot Springs County Pioneer Association. We are dedicated to preserving the history of our unique county and city of Thermopolis.

This podcast was supported in part by a grant from the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, a program of the Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources.

This was a production of Legend Rock Media Productions.

Music Credits:

- Rattlesnake Railroad by Brett VanDonsel

- Roundup on the Prairie by Aaron Kenny

- The Gunfight by Everett Almond

- The Old Chisholm Trail by Harry McClintock (1928)

- Celtic Impulse by Kevin Macleod

- A Fallen Cowboy by Sir Cubworth

- Western Spaghetti by Chris Haugen

Be sure to subscribe to “Pioneers of Outlaw Country” so you don’t miss a single episode of this historic series.

Your hosts are Jackie Dorothy and Dean King and you can find us at (20+) Pioneers of Outlaw Country | Facebook

We also have a great deal for you! We have used Sonix for all our transcriptions for over five years and believe they are the best in the industry! Give them a try with our referral code and see why we are loyal customers! https://sonix.ai/invite/kldawrg

This is a production of Legend Rock Media Productions.

Hot Springs County Pioneers Presents: Tim McCoy

He was a man of the West. A cowboy, rancher, friend of the Indian warrior, cavalry officer, Hollywood movie star, and showman.

He lived by the adage, “Never look back; something might be gaining on you.”

This son of Irish immigrants was a true pioneer of Hot Springs County, Wyoming.

During his lifetime, Tim McCoy was one of the most famous men who called Hot Springs County, Wyoming home.

In the early days of film, he was one of the Big Four of Hollywood Western Stars alongside Tom Mix, Ken Maynard and Hoot Gibson. He starred in over 100 movies, had his own tv show, won an Emmy and his star is on Hollywood Boulevard.

Today, many people never heard of Tim McCoy even in his hometown of Thermopolis. Tim McCoy’s early years were tied to Hot Springs County and he ranched up Owl Creek at the Eagles Nest for 30 years. He often said that his heart belonged to Wyoming – not the glitz and glam of Hollywood.

Just who was he?

Well, he was the All-American cowboy that found his way to Wyoming in the early 1900’s. Tim McCoy grew up in Michigan, the son of Irish immigrants. His first exposure to the Wild West was as a seven-year-old at the Wild West Show in Saginaw. He met Buffalo Bill backstage and was awed into silence. Later, as a young man, he spent time at the freight yard where wild horses were sold and the main attraction were the cowboys that tamed them. After a cowboy he knew only as Bob taught him how to rope a half-wild bronc, McCoy was determined to became a part of this exciting life.

In 1909, at age eighteen, McCoy slipped away from school and, without telling his parents, took off back west to be a cowboy --- although he had no idea where he was going. Oklahoma? Nebraska? Montana? Arizona?

A chance meeting on the train with a bronc rider from Lander took McCoy to Wyoming. By that fall, he joined the Double Diamond’s roundup as a horse wrangler.

The Double Diamond outfit was part of a conglomerate known as the Mill Iron Cattle Company composed of the M-Bar, the Circle and the Double Diamond ranches.

From its base along Wind River and Owl Creek, the Mill Iron Cattle Company monopolized the surrounding Wyoming country. Tens of thousands of their cattle ran loose for miles and miles along the vast, unfenced range land. It was owned by Jake Price and Colonel Terry – the same men who had sent their former employee, Butch Cassidy, to prison for stealing their horses.

During these early years, rustling was rampant on the open Wyoming range. Even with this daily threat of theft, the Wyoming Cattlemen’s Association would not allow cowboys to carry a pistol on roundups. According to their rules, having a firearm on your side could be grounds for immediate dismissal.

The cowboys were, however, allowed a Winchester rifle as long as they kept it attached to a saddle. The hope was that this no handgun rule would keep the cowboys from shooting each other during the tense and dangerous roundups.

For eight years, Tim McCoy rode the Wyoming countryside on these roundups for other men. Like many of the young cowboys of this era, he worked on several ranches, moving on when the pace grew too monotonous and looking for new adventures.

After just one season at Double Diamond, Tim McCoy left Lander and rode into Thermopolis. After deciding he wasn’t a ‘bad one’, the sheriff directed him to a job with Irish Tom Walsh. McCoy joined Irish Tom’s Outlaw Train and worked alongside the likes of Henry Rothwell, the upright college graduate and Frank James, a former member of the Hole-in-the-Wall gang.

Irish Tom was a cattleman who lived in Thermopolis because he didn’t actually have a ranch. However, he and his partner, the town banker, owned a large number of homesteads which were scattered all over and controlled most of the area’s springs. As a result, they ran a far-flung cattle outfit.

When Tim McCoy met Irish Tom, he was about fifty years old and walked stooped over which helped him earn his other nickname. Throughout Hot Springs County he was known as Irish Tom, the Boar Ape.

When McCoy arrived in Thermopolis in 1910, the streets were dirt and and all but one building were made of wood.

McCoy said that by the time he arrived to town, Thermopolis was becoming a respectable place – more or less. However, even in his day, some strange characters continued to move in and out of the town. They tended to blend in, using the town’s 3,500 inhabitants and visiting cowboys as camouflage. These men included those known as Toughey, Smooth and Jack-the-Dude.

That first day, Tim McCoy didn’t have much time to explore the town or meet these colorful men. Irish Tom hired him on the spot and took McCoy that very afternoon to a line camp at the head of Buffalo Creek.

Two cowboys already lived in the one-room house, which was fashioned from the local sandstone. To the side of the house was a small corral where the saddle horses were kept.

The cowboys were Wicks Duncan, described by McCoy as a husky, quarter-breed Shoshoni and an outstanding cowboy that could ride almost anything with four legs. The other cowboy was Henry Rothwell, son of the owner of the Padlock Ranch and a cool, practical cowboy who had just returned from college in the East.

Seven more men were recruited for the roundup and within a few days, the cowhands were out collecting the widespread cattle.

According to McCoy, after the herd was collected in scattered groups during the day, they were then bunched together at night and added to on the next day. As the herd grew larger and larger it had to be handled right and held tight at night so the beeves didn’t drift away or stampede.

Two-man guard teams worked through the night, one riding clockwise and the other riding counterclockwise to keep the cattle together. And this is where the legend of the singing cowboy was born.

It didn’t take much to spook the half-wild cattle. If a man were to stop to light a cigarette, the flash of the match would be enough to spark the beeves into running. The jingle of saddle leather or any other sound could also set them off. In order to keep them calm, the cowboys would sing as they rode the night circle. The cattle became accustomed to their voices and common tunes included Chisholm Trail and Sam Bass.

Tim McCoy had a beautiful tenor voice and instead of the usual “Texas songs”, would sing the soft, lilting music of his Irish childhood. If he was on early guard, the other cowboys would lie awake, listening to his singing under the wide Wyoming sky.

One night, McCoy was sitting around the fire at suppertime when someone asked who was on second guard. The answer from Irish Tom was “Ted Price and the Canary.”

McCoy protested, “Wait a minute – I’m on guard with Ted Price.”

Frank James, still a half-outlaw, answered, “Hain’t ya heard yer name yet, young feller? You’re Irish Tom’s Canary.”

The name stuck and followed McCoy as he roamed from ranch to ranch.

When Tim McCoy worked for Irish Tom’s outfit, it was what was called a “pool wagon”. The ranchers with small homesteads on the other side of the Big Horn such as Kirby, Buffalo, Alkalai and Bridger creeks had small herds of one to three hundred cattle. They could not run roundups on their own so would join Irish Tom’s roundups with one rep to keep an eye on their own cattle.

It was a great arrangement with one drawback.

Impoverished cowboys who wanted to go into the cattle business would be part of the “pool wagon”. They didn’t have money or cattle – just a long rope, fast horse and an ‘idea’.

This idea meant that there were so many rustlers in Irish Tom’s wagon that throughout the Big Horn Basin, it was known as the Outlaw Wagon.

The rustlers were not taking large herds like seen in the Hollywood movies but would take out a few unbranded cows at a time so they would not attract too much attention. Slowly these rustlers would build their own herds by driving the unbranded calves into the brush and leaving them there until they could quietly retrieve their ‘new’ cows later.

Another technique of rustlers was to butcher branded yearlings and take the beef to less-than-scrupulous butchers. Proof of the ownership of the cow was through the hide and the butchers would claim ignorance about old hides being used over and over rather than the required fresh hides.

Even during Tim McCoy’s time on the range, the large cattle operators, angry at losing so many of their cattle, employed fast guns to take care of these small-time rustlers. Cowboys that McCoy knew personally began to fall to these guns.

Known as “regulators” and “bushwhackers”, news would move fast when one of these assassins was spotted in Thermopolis and the tension would mount until one day, a lone cowboy would be shot from behind, falling lifelessly from his saddle.

One of these well-known regulators of the area was Sam Barry.

In 1912, Tim McCoy was at Happy Jack’s Saloon when Barry walked in. The mood altered immediately from loud and boisterous to the ambience of a funeral parlor.

All Barry had to do was to show his face and rustling went away. He was well-known to have personally collected blood money on accused rustlers, cutting off their ears as proof of his kill.

Living on the edge of the outlaw era, Tim McCoy personally met many of the colorful characters that once ran around the lawless countryside.

As a curious young cowboy, he asked many questions about the past from the old-timers. He spent time with former outlaws, such as Walt Putney, who shared their stories – now that the term limits had expired on some of their crimes.

Another famous individual that Tim McCoy spent time with was Buffalo Bill Cody.

Between 1912 and 1916, when on cattle-buying trips or month-long breaks from cowboying, McCoy would go to the Irma Hotel, built by the famous showman.

Often Buffalo Bill himself would be there, regaling his audience with tales of old. McCoy was one of many young cowboys who stood within earshot of the legend to listen to his stories.

This exposure to the great showman had an influence on McCoy for by 1917, bearing his nickname Irish Tom’s Canary, McCoy had made the front page of the Thermopolis newspaper with his musical production, “Talk of the Town.”

He had gathered together local talent and personally performed songs that stole the show. Amid high praise for his talent and musical abilities, McCoy became a sought-after entertainer.

Hints of his future in Hollywood were seen in the newspaper write-up of the performance he gave for the Wool Buyer’s Association…

“Tim McCoy proved to be an all-round entertainer who put pep into the doings. His anecdotes would be among the best sellers if put in print, and a general gaiety man his equal would be hard to find. The cabaret girls were credited with being sophisticated, but when the Irish Canary got on the stage and mixed things up with them, the best they could do was to play second to his lead.”

By now, McCoy had his own spread, the Eagles Nest, in the Owl Creeks above the Embar. On the isolated Eagles Nest ranch, the McCoy family’s mail was delivered by horseback by their neighbor, 10-year-old Ken Martin. The youngster would regularly take his horse to the post office at Embar, below McCoy’s ranch and, on his way home, Martin would stop to drop off McCoy’s mail. Martin remembered those years fondly of his rides through the sagebrush and grew to admire Tim McCoy who was grateful for the mail deliveries,

But McCoy wasn’t content to stay at home.

The year of 1917 brought Tim McCoy to the military. World War One was raging and in a burst of patriotic pride, he penned a letter to Theodore Roosevelt, offering to recruit a full squadron of four hundred cavalrymen from among the cowboys of Wyoming and Montana for the Rough Riders.

Two weeks later, a telegram arrived stating simply, “Bully for you! Do proceed! Roosevelt!”

Armed with this directive, McCoy took two months to get four hundred men signed up for his squadron. To recruit his soldiers, he would ride into town on a Friday and make the rounds of the saloons.

However, President Woodrow Wilson axed the Rough Riders war effort and the cowboys remained at their jobs on the range.

That wasn’t the end of Tim McCoy’s military endeavors. Through his persistence, he joined the army and rose in the ranks to Major.

Once the war was over, Tim McCoy and wife, Agnes, returned to Thermopolis. By 1919, the cowpoke was promoting Wild Shows with his friend, R. J. Price, another cowboy seeking the stage life.

McCoy’s personal career continued to expand. In early 1920, he was made the Adjutant General for Wyoming and it was while in this position that he got his ticket to Hollywood.

It was 1922 and Tim McCoy had been the adjutant general of Wyoming for just under three years. At 31 years old, he owned a ranch on the Owl Creek that had been expanded to 25 hundred acres with another 25 hundred leased from the government. He ran a herd of 350 cattle and had three children. But -- in his words -- he was bored.

That was when Hollywood came knocking. Over the years, Tim McCoy had made several lifelong friends among the Arapaho Indians and had learned the sign language of the plains.

An epic silent movie, The Covered Wagon was being produced that required 500 Indians to play as extras. McCoy was asked to supply these men and, along with Ed Farlow, did just that. They got members from several tribes to come together for the movie.

Before the Covered Wagon even opened in early 1923, Tim McCoy was already getting offers to star in his own movies.

Although the first attempt, an adaption of a movie called Dude Wrangler, was not filmed as hoped in Thermopolis, McCoy went on to star in over 100 Western films.

He began his career in the silent movies and, because of his singing abilities, was one of the few actors able to make the transition to ‘talkies’.

In 1935, while still staring in B-movies, McCoy joined the circus.

For three years, he performed in the fall for the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Baily. Astride a palomino horse he secretly despised, McCoy would do trick shooting and lasso tricks during his Wild West performances.

On April 14, 1938, in the midst of the Depression, the enterprising cowboy launched “Tim McCoy’s Wild West and Rough Riders of the World” in Chicago. The show only lasted 21 days and McCoy lost $300,000 in the process.

When his Wild West show venture failed, McCoy returned to the movies. World War II then called him back to action and he risked his acting career to go answer the patriotic call. When he returned back to the states, he found that there wasn’t much work for 54-year-old cowboys in Hollywood.

Before retiring in Pennsylvania, Tim McCoy returned to Thermopolis and sold the Eagles Nest to a neighboring rancher and former boss, Landis Merril. Merril’s grandson and namesake, Landis Webber, recalls being present at the sale when his grandfather purchased the ranch. The family remembers McCoy well.

As Webber tells it, while working at the Embar, the young Tim McCoy stole a dress off the clothesline for his girlfriend Blanch. He was fired from the ranch for his youthful prank and soon after, the likable McCoy began his career as a promoter and bought his own place.

Another family story claims that Tim McCoy was one of the many bootleggers who plied his moonshining trade during the controversial prohibition years, entertaining visitors at the remote Eagles Nest. These stills were tucked away in isolated ravines and the whiskey enjoyed by even the most upstanding of Thermopolis citizens.

Selling the ranch wasn’t the end of McCoy’s visits to Thermopolis. In 1966, he returned to put on a Cowboy Poetry show and sang songs. He invited his old friends to attend and regaled them with a performance from the past.

Among the attendees, now a warden in Jackson Hole, was Ken Martin, the ten-year-old boy that used to deliver his mail on horseback.

When Tim McCoy wrote his memoirs, reflecting on his adventures, he told the story of his years in Wyoming rather than his glamourous life in Hollywood.

Wyoming is where his heart belonged. We will leave you with the poem he wrote about his home of Thermopolis that was published in the Thermopolis Independent on May 27, 1920… Passing of the Cow Town

… When cowboys sang the Chrisholm Trail without a shred o’ tune,

When heads reared back like coyote pups a-bayin’ at the moon.

And when a toast was bellered out, it made the rafters quiver,

As fifty iron-throated birds responded, “Powder River.”

With Wildcat Sam resplendent in his California pants,

And Hambone Bill emergin’ from a ten-day whiskey trance,

Ol’ Pacin Daley tellin’ bout the days of forty-nine

And Jim McLeod a tryin’ hard to sing, “Sweet Adeline.”

They say that times are better now since progress drifted in

An’ prohibition rescued us from leadin’ lives o’ sin.

But I’ll say this much for progress as her wheels about us buzz;

Old Thermop is sure some village – but she’s nuthin’ like she was!

Thank you for listening to Hot Springs County Pioneers. Be sure to subscribe so you don’t miss a single episode of this historic series. The stories of our pioneers were brought to you by Hot Springs County Pioneer Association.

This podcast was supported in part by a grant from the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, a program of the Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources.

This was a production of Legend Rock Media.