Pioneers of Outlaw Country: Wyoming History

Pioneers of Outlaw Country: Wyoming History dives deep into the rugged, untamed spirit of Wyoming's rich history.

Many of these stories have been forgotten and the pioneers are relatively unknown. Join us for a journey back into time that is fun for the entire family and students of any age!

This podcast series has been supported by our partners; the Hot Springs County Pioneer Association, the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, a program of the Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources, the Wyoming Humanities, and the Wyoming Office of Transportation.

Pioneers of Outlaw Country: Wyoming History

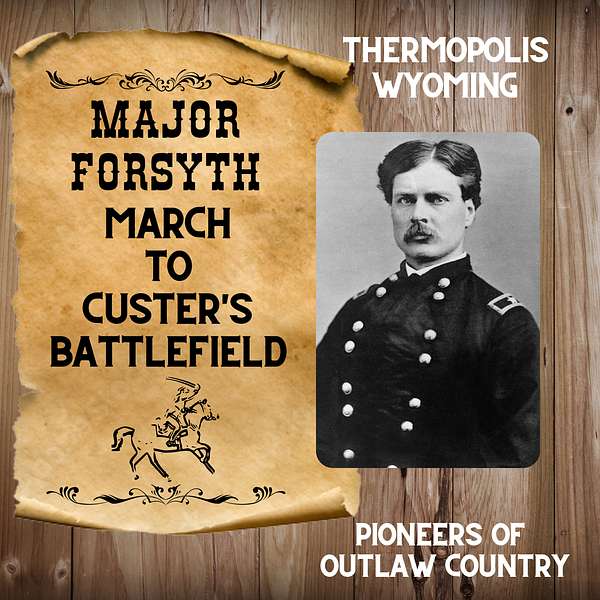

Major Forsyth; March to Custer's Battlefield

Major George “Sandy” Forsyth: His Forgotten Diary

He was a Civil War veteran, Cavalry Officer, Indian Fighter, General Sheridan’s aide de camp, avid fisherman, author, husband and Brigadier General.

This courageous soldier was a true explorer of Hot Springs County, Wyoming.

The Pioneers of Outlaw Country.

Cowboys, Lawmen and Outlaws… to the businessmen and women who all helped shape Thermopolis and Hot Springs County, Wyoming.

Here are their stories.

Major George “Sandy” Forsyth: The Forgotten Diary

In the Hot Springs County Museum in Thermopolis, Wyoming, a nondescript brown journal was displayed without acknowledgement of its historical importance. This journal was on display in the military exhibit with a small photo of its author, Major George “Sandy” Forsyth.

Someone had stamped the cover with the old address of the County Museum before that museum was burned and moved to its present location on 700 Broadway in Thermopolis, Wyoming. Somehow, the journal survived the devasting fire although its outer edges are tinged with old soot.

This journal was on its way to the Smithsonian when instead, the owner chose, through a series of twists and turns, to send the journal to Thermopolis. That is because this journal was written in 1877 about a journey through the future Hot Springs County.

Major George “Sandy” Forsyth was General Sheridan’s aide de camp and, along with many notable officers of the time, was on a journey through the Big Horn Mountains to Camp Custer. It had been one year since General Custer had been killed at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. The company of soldiers, who had all known him and his regiment, were on their way to the new posts being built along the Rose Bud and Tongue River. The Indian Wars were coming to an end and the company was accompanied by Sioux Scouts.

They had left Chicago on the train and arrived in Cheyenne within one day. From there, they took the train and stagecoach to Camp Brown, a fort near the future town of Lander. This trip was unlike any from the previous years when danger lurked on the countryside from hostile Indians. The Indian Wars were over and now the soldiers hunted and fished their way across the beautiful landscape.

Sandy Forsyth was a skilled writer and his words describe a world as beautiful as any park. He describes the bright blue of the larkspur and forget-me-nots, the string of trout they caught and the mosquitoes that plagued them. In 1877, buffalo still roamed Hot Springs County in large herds and the area was still being mapped.

Be sure to subscribe to “Pioneers of Outlaw Country” so you don’t miss a single episode of this historic series.

Your hosts are Jackie Dorothy and Dean King and you can find us at (20+) Pioneers of Outlaw Country | Facebook

This is a production of Legend Rock Media Productions.

Over the Stage Line to Thermopolis

They were adventurers, farm boys, prospectors, family men and former soldiers. These men who drove the stage through Wyoming had to be endure the heat of summer and the sleet and snow of winter... and bandits.

These hardy stagecoach drivers were true pioneer of Hot Springs County, Wyoming.

The Pioneers of Outlaw Country.

Cowboys, Lawmen and Outlaws… to the businessmen and women who all helped shape Thermopolis and Hot Springs County, Wyoming.

Here are their stories.

Over the Stage Line to Thermopolis

Driving the stage could be dangerous business.

Early in his career, coal miner John Hultz drove stage over Birdseye Pass which took him from Shoshoni to Thermopolis over steep grades and miles of lonely wilderness. This route began in late 1905 when travel over Mexican Pass was halted by the tribes.

One summer day, John was driving the stage on Birdseye when two men tried to stick him up. He said that one little fella climbed up on the wheel and pointed the gun in his face. At the same time, the other bandit climbed up on the right side and put the gun on the man that was riding shotgun.

“We want your money!” they yelled.

Somehow in the commotion, the man with the shotgun distracted the other bandit and John said he knew that this little guy was scared because his gun kept shaking.

He was so out of control with shaking that John figured that no matter what happened, he was going to get shot so John started shouting and wrestled the gun away.

The other bandit bolted when he saw the robbery going awry but the scared thief was hauled in to jail.

Another time, John recalled an accident when the wheels came off his wagon as they were on the Pass. The stagecoach turned over and his passenger, a lady sheep rancher, was left behind. John’s brakes wouldn’t work so it was some time before he could go back and rescue the stranded passenger. Her only injury was a ‘bum knee’.

Sometimes, he said, the snow was so thick that he had to make everybody get out and just let the horses try and pull the stage through the snow.

In the fall of 1898, seven years before Birdseye Pass was used as a route, the Casper and Thermopolis Stage Line opened for business. The Big Horn River pilot ran a small ad announcing that the stage was prepared to carry passengers and express. They would run daily, except Sundays, and the new proprietor R. H. Wagner, guaranteed reasonable prices.

There might be reasonable prices, but not always realiable drivers as one hapless pioneer learned. It was Thanksgiving Day and Dora McGrath was riding to Casper, on her way home from a trip to visit her sister in Thermopolis. As she traveled over the old Bridger Trail, she had the full experience of a stage coach ride with all the thrills.

For some reason, a boy was driving that day and the two teams hitched to the stage were broncs. The boy carelessly stepped out on the brake block and frightened the broncs. Away they flew, jerking the lines from his hands. There was nothing for the occupant of the stage to do but sit still and hold tight. Tearing frantically along, one bronc stepped into a prairie dog hold and down went both teams with the stage rolling over, Dora McGrath underneath. The boy driver finally managed to poke a hole through the top of the coach, crawled out and pulled Mrs. McGrath out after him. Her injuries did not prove to be serous after a day or two of rest.

In August of 1901, a journalist introduced readers of the Natrona County Tribune to this stage line, letting them know exactly what to expect on a more uneventful trip.

If you have never made a trip on the stage from Casper to Thermopolis in thirty-six hours, a distance of 140 miles, then you have missed something in this life which you would remember until your last day. Being up for two nights and a day seems hard, but we assure our readers that they would be kept awake along the entire route, and they would have a good appetite at all the meals.

You leave Casper at 9 o’clock in the evening, with a four-horse team ahead of you. After traveling west for fourteen miles you come to the first relay station, where the four horses, which have been going at a continual trot all the way, are unhooked and four fresh horses take their place; in five minutes you are again heading west at a full trot.

About midnight you pass the “stone ranch,” where O. K. Garvey is living, and has been running the past year. In another hour or two you come to the “Casper Creek Road Ranch, which is now under the management of Ballard & Steed. A small mail-bag is dropped off at this place, but no one was disturbed from their slumbers.

You hit the road again, and keep time with a nod of your head to all the ruts and jolts encountered until you reach William Clark’s home ranch on South Casper Creek, about 2:30 in the morning.

You are fed breakfast here, although it is somewhat earlier than most of us are accustomed to eating breakfast. You will, nevertheless, enjoy the meal, for Mrs. Clark and her daughters are well aware how to set a nice breakfast. The good cooking and the hospitality of the hostess are indeed a comfort to tired mortals who have been bumping along the road all night long.

After you finish your breakfast and have a little social chat with Mrs. Clark, you make your way out to the stagecoach and get ready to proceed on your journey. At Clark’s ranch is where you notice the first break of day in the east, and you feel more like lying down on the ground and taking a nap than hitting the trail again. But, just as sleep is beckoning you hear the driver’s “ALL ABOARD,” and in a minute you are again heading west on a swift trot, as another fresh team of four horses has been hooked to your chariot.

When Mr. Clark’s ranch is a few miles behind you the sun makes its first appearance, and you can see some evidence of life on the lone prairie. Now you are traveling along what is known as the “hog-back of the Powder River country.” There is not a freighter who has ever been along this road in wet weather but who knows all about the hog-back, for when it rains or snows the horses sink in the gumbo up to their bellies, and the wagon wheels go down as far as their hubs. These few miles of road has caused more profanity from freighters than all the rest of the road between Casper and Wolton. Consequently, someone has named this particular spot, “The Freighter’s Delight.”

After getting well up on the hog back, you come to what is known as “Hell’s Half Acre.” It is a patch of ground which has the appearance of at one time containing a bed of coal, and the coal having been all burned out. There are deep sinks in the ground, almost a half-mile deep, and peaks sticking up in all shapes and sizes. It is truly half an acre of good-for-nothing land.

After leaving this spot and traveling for several miles you meet the east-bound stage, which is bringing all the mail, express and passengers from Lander and Thermopolis to Casper. You get a squint of those dusty passengers, and wonder if they are as tired and sleepy as you are—and from the way they look at you, they are probably wondering the same thing about you.

Another change of teams is made at Keg Springs, where Martin Oliver is the stock tender. Eight miles more and you reach Wolton, where you are greeted by Oliver Johnson, the postmaster and general manager of the Wolton Commercial company’s store. He will talk business with the driver, chat with the passengers, and wait on customers all at the same time. Oliver has sheep interests in the vicinity, and the management of the store at Wolton is so close to his monied interests, that he is perfectly satisfied with his lot. Genial Tom and Mrs. Hood are living in Wolton, where they have management of the hotel …

The Cooper Dipping Plant is located here, as well as large shearing pens, and many thousands of sheep are shorn here each spring, and given a good hot bath in a solution which Mr. Holliday says is the best remedy on earth to cure scab, and give sheep a clean, nice-looking fleece. Hundreds of sacks of wool are stacked here from early spring until late in the summer, waiting for freighters to come along and haul them to Casper for shipment east on the railroad.

After the mail is transferred and the express is unloaded, the passengers are again told to all get aboard, so you arouse yourself from any pleasant dreams you are having, or tear yourself away from an interesting conversation and start for Round Hill. There you will take dinner, and perhaps get a little sleep before changing “cars” for either Lander of Thermopolis.

Everything is unloaded from the coach here and divided up for the two branch roads, one leading to Thermopolis, and the other to Lander. Round Hill Station is looked after by Mr. and Mrs. George Demorest, Mr. Demorest looking after the stock and Mrs. Demorest attends to the comfort of the “inner man” of the passengers. She gets up a good meal, but as a general thing most passengers are too tired and sleepy to enjoy eating.

After dinner the weary passengers lay down in the barn, out of the hot sun, and many are snoring away when they feel a jolt in their ribs and awaken to find the driver is about ready to leave on the final seventy-five miles of the trip, which will require the balance of the day and all the next night. You get a new driver here, and if it happens to be Gene Brown, you are sure of a safe trip, for he is not only a careful driver, but he can make better time and allow the horses to go slower than any man you ever rode with.

You start out across the burning sand and alkali flats for Thermopolis. What the Lander passengers might see along the road that is interesting, we know not, for we have never gone that route. But, the Thermopolis passengers experience the hardest part of the trip between Round Hill and Lost Cabin, for it is done during the hottest part of the day, you pass along through about six miles of alkali flat, and the road is very rough.

About 3 o’clock in the afternoon you reach Lost Cabin, where there is a long lost gold mine, which Mr. Okie found a few years ago when he put up his general store. There are a number of buildings at Lost Cabin, and the elegant mansion of Mr. Okie, which is almost completed. The mansion is indeed a treat to the eye, after coming in from the miles of waste and desert that you have been traveling over all day.

After transacting the necessary business at Lost Cabin, the driver again shouts “all aboard,” and the coach starts across country headed for a mountain peak, which you are informed you must cross over before you get supper. At first the mountain looks about twenty miles away, but after the driver informs you about supper it looks to be twice that far away.

A few hours from Lost Cabin you come to a steep hill, which looks almost impossible for a team of horses to descend with a wagon. The driver stops and rough-locks the wheels, and makes an examination of the wagon and harness. If everything looks all right, you suddenly pitch downward. When you get to bottom you say to yourself that if you ever go down that hill again, you will get out and walk down.

This is called Moore Hill, because it is only a short distance from the ranch J.W. Moore once owned on Bridger Creek. M. L. Bishop is living on this ranch now, and is stock tender for Mr. Clark’s stage line. Another change of horses is made here, and once again you start for the mountain which you must pass over before you get supper.

You travel along the valley of Bridger Creek, in which are located many prosperous ranches; the first after the Moore ranch being the Rider ranch, where Mrs. Rider and her daughter Minnie live, and thrive on their little garden. They also have some stock running out on the range.

We notice Minnie coming up from the creek, where she had been watering horses and other stock, but her manner of riding was not appropriate with her style of dress, and she quickly made an escape into a nearby draw and out of our sight as soon as she noticed the stage. The next ranch up the creek is owned by Samuel Warden, and a great deal of valuable land, which has not yet been cleared of sagebrush. But, he has a nice garden spot, and has the reputation of furnishing the nicest lot of garden truck to passersby of any in this part of the country.

A little farther up the creek you come to DeRanch, where William Long has made his home for years. He has one of the nicest and most valuable ranches in this valley. He has a large tract of land cleared, and raised and puts up hundreds of tons of alfalfa each year. Mr. Long is postmaster at DeRanch, and all the settlers on Bridger Creek receive their mail at this office.

After you leave DeRanch you commence to climb the mountain, on the other side of which you are promised dinner. But, it is already beginning to get dark, and it is a two-hour’s ride before you will get to the Mountain Home ranch. You commence to realize that meals are far and few between.

The horses must necessarily travel slow up the mountain, and the weary passengers are beginning to suffer from a combination of hunger, thirst, sleep and fatigue. After a long pull of an hour or more, the stage finally reaches the top of the mountain, where the horses are given a short rest. Then you start to slide down the other side of the mountain, where you strike the head of Kirby Creek and Tom Clark’s ranch.

Mr. Clark has a nice ranch house and a band of sheep which he runs on the nearby range. You are attracted by the lights from his camps as you glide by on your rapid rush to supper. It is about 10 o’clock p.m. when you finally reach Mr. Clark’s home ranch, where Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Burgess are in charge. This is the place you’ve been looking for, for a long time, and when you get your feet under the table, you are not disappointed.

There is where you get one of the nicest meals along the entire route. Mrs. Burgess seems to know just what the weary traveler most desires. She is an excellent cook, and the man who is not satisfied with the meal he gets here, is indeed hard to suit. A man never took a meal at the Brown Palace or Palmer House that gave such satisfaction as the one he gets at the Mountain Home ranch.

After supper, if the stage is on time you are allowed to rest about 10 minutes while a fresh team is hitched up. Soon you are off for Thermopolis, which is forty miles distant, and which will require an all-night’s drive before you reach there. The are many interesting sights along this stretch of road, if you have any desire to look for them.

The first and most interesting is a stone chimney, which has stood on the lone prairie since the early 50’s. Two hunters and trappers built cabins at this lonely place—they were the first white settlers in this part of the country. They had not been here very long before the Indians found them, burned their cabins and killed the settlers. But, their chimney has remained there undisturbed for all these years, and serves as a headstone for the white men who lost their lives in those early years.

You travel on and on, even getting a little sleep now and then when a smooth stretch of road is reached. But, you are awakened so often that it is only an aggravation trying to sleep. So, then you brace yourself up and take a look at the countryside in the moonlight.

About daybreak you reach the turbulent waters of the Big Horn River. Then you come to Andersonville, and across the river you will see where the old town of Thermopolis was located just three years ago. There is a schoolhouse at Andersonville in which Miss Caan is teaching the summer term. She has about a dozen scholars, but where they come from is beyond the power of the human eye to see.

Thermopolis is six miles from here, but it is the longest six miles we have ever yet traveled. You pass over hills, through canyons, around creeks and curves, and by the time you reach town you are certain you have traveled at least ten miles from the little schoolhouse seen along the wayside.

You finally reach Thermopolis, completely tired out and exhausted; the first thing you do is look for a bed in which to fall, where you plan to sleep the sleep of the tired and weary pilgrim far from home. After remaining in bed all the rest of the day and the following night, you are ready to go over to the hot springs and take a bath to relieve yourself of some of the real estate you have accumulated on your person along the stage route.

It requires 125 head of horses to keep the stages moving on this route, and there are at least twenty men employed. It matters not what kind of weather we have, the coaches must be kept on the move. They carry the U.S. Mail, and like time, the mail waits for no man.

Mr. Clark has conducted this line for lo these many years, and had given universal satisfaction to the government and the passengers. Everyone hopes he will again be awarded the new mail contract this fall, after his present contract expires.

Thank you for listening to Pioneers of Outlaw Country. We are your hosts, Jackie Dorothy and Dean King.

Be sure to subscribe to “Pioneers of Outlaw Country” so you don’t miss a single episode of this historic series. The stories of our pioneers were brought to you by Hot Springs County Pioneer Association.

This podcast was supported in part by a grant from the Wyoming Cultural Trust Fund, a program of the Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources.

This is a production of Legend Rock Media.